25 Feb FACTS ON ETHNIC ELDERS: Little Help for Prisoners Released After Decades

News Feature, Paul Kleyman | New America Media

After devoting over 20 years as a prison social worker, Fordham University researcher Tina Maschi, PhD, declared, “There’s something wrong with society when in some ways staying in prison is better than getting out. The people who are older have a much greater struggle, because they have special needs that a younger population doesn’t.”

Current efforts to release prisoners from the nation’s overcrowded and increasingly costly prisons, such as U.S. Attorney General Eric Holder’s new initiative to let out more nonviolent federal inmates, barely touch on the needs of older inmates, which Maschi and other researchers say will be more likely to be paroled because of their high health care costs and low recidivism rates.

Yet, even the 15 states that developed early-release programs for senior prisoners, according to a 2010report by the Vera Institute of Justice, need to “implement effective reentry programs and supervision plans for elderly people.”

America’s escalation of harsh sentencing and probation policies since the 1970s, such as three-strikes convictions and mandatory sentencing laws, swelled the United States prison population to 2.4 million, the highest incarceration level in the world.

Some End Up Homeless

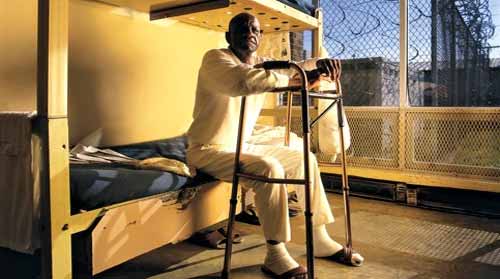

One result of long-sentencing policies, said Maschi, coauthor of the forthcoming book chapter, The Crisis of Aging People in Prison (Oxford University Press), is that one-in-six state and federal inmates is 50 or older—a level that will increase to one in five by 2030. Nationally, a disproportionate 45 percent of 50-plus prisoners are African American.

Advocates like Jamie Fellner of Human Rights Watch say medical treatment of elderly prisoners costs from three to nine times higher than for inmates under 65 and can turn prisons into “nursing homes without bars.”

When they are set free, older offenders “can be dropped off on a corner somewhere,” Maschi said in an interview. She explained, “People are getting out, and if they’re eligible for Social Security, Medicaid or Medicare, they don’t have that put in place before they are released.”

Maschi stressed, “Many people end up homeless, and if they end up in shelters, they are at risk of being robbed or [becoming a target] of violence, which is shocking. They say they’d rather go back to prison, because at least you’re getting regular meals and a secure place to sleep — ‘the three hots and a cot.’” Violent as prisons can be, she added, unlike shelters they have officers on hand to keep the worst abuses in check.

She recalled one man she met in her research: “Even though he had a job, he was still homeless two years after being out of prison. He just wasn’t being paid enough, and he didn’t have a major diagnosis that could get him support — substance abuse, mental health or HIV. So he was in this catch-all category, where he couldn’t get services.”

Major obstacles to reentering community life, Maschi said, are housing, employment and health care. She cites a 2010 Pew Charitable Trusts study showing that released prisoners typically earn no more than half of what they made before incarceration.

She continues, “If you get out, you’ve barely earned any Social Security, and you have to start from scratch. Some of the reentry organizations will simply say, ‘Go apply for something,’ so they don’t necessarily provide assistance.”

Barriers to Successful Reentry

Beyond practical help, Maschi said both service professionals and aging former prisoners in her research say they need emotional support: “They need a network. That seems key. And family, if they have family.”

“The biggest hurdle that a person faces when he comes home from prison,” said Lawrence O. ‘Larry’ White—“is what they call collateral consequences”—especially psychological stress and community bias against former felons.

White, 79, faced the struggle of reentry after serving a 32-year sentence for robbery in New York State prisons. He explained that released inmates are told they are rehabilitated and need only to improve themselves to start over.

He should know. White has devoted over two decades both in and outside of prisons developing workshops and support groups for prisoners—working through organizations such as the Fortune Society prisoner-support organization and Fordham University’s Be the Evidence Project.

For instance, his “Sentence Planning” courses have helped prisoners refocus their attitudes and energies on serving the shortest sentence possible and preparing to rejoin their communities.

But communities also need to change, he said. Once on the outside prisoners initially believe, “I’ll get a skill or training, I’ll get me a job, get my home in the country, have a dog named Spot, and I’ll move up to the American dream.” They soon learn, though, that a felony conviction frequently locks them in a box—such as the box on applications asking, “Have you ever been convicted of a felony?”

White stated, “Once you check that box, you’re dead–your ability to improve your quality of life by getting a job, new place to stay, even going to college is out the window.”

Eliminating those boxes, as Target stores did in November on its job applications is only one of the crucial reforms experts recommend to remove employment hurdles for former prisoners. (To date 10 states and over 50 cites—most recently San Francisco–have passed laws to “ban the box” on job and housing applications. Employers can consider applicants’ criminal justice records only after deciding to offer them a position.)

Bridges to Community

White, paroled in 2007, considers himself fortunate to have his basic needs covered. Like most long-term inmates, he earned too little while incarcerated to contribute to Social Security. But he qualified for $800 per month from the program in survivor’s benefits due to his late wife’s work history, plus $160 in food stamps.

He lives in a low-income subsidized studio apartment at a fairly new building in Manhattan developed by Fortune Society.

Although he has found regular wages hard to come by–“Nobody wanted to hire me because of my age”– White has been able to supplement his income now and then through fees from leading courses for nonprofits when they can receive grants to work with the prison population.

Medicare and Medicaid cover him, including surgery for cancer that doctors told him was not caught early enough in prison, and recent fainting spells linked to an irregular heartbeat.

Starting this year, about 9 million low-income former inmates are eligible for Medicaid coverage under the Affordable Care Act, but only in the 26 states and district of Columbia that agreed to expand the health care program.

Overall, Maschi stressed, that when it comes to post-release, “Even if you’re fairly well functioning, there’s nothing for you if you’re older.”

She and colleagues have cited model reintegration efforts, such as the Senior Ex-Offender Program based in a San Francisco Senior Center and England’s Restore 50+ support network. But these are few and far between.

In her book chapter, Maschi and her coauthor note, “Providing a seamless bridge between prison and community is not only a key component of providing individual, family and community cohesion, it may also reduce the $60 billion in reentry costs that will increase as more prisoners age with complex health and social care needs.”

Paul Kleyman wrote this article as part of New America Media’s initiative on elders’ income security, with support from The Atlantic Philanthropies.

No Comments