08 Sep Q & A: Bill Jennings on Black Panther Party’s Place in Richmond’s History

Interview, Steve Early

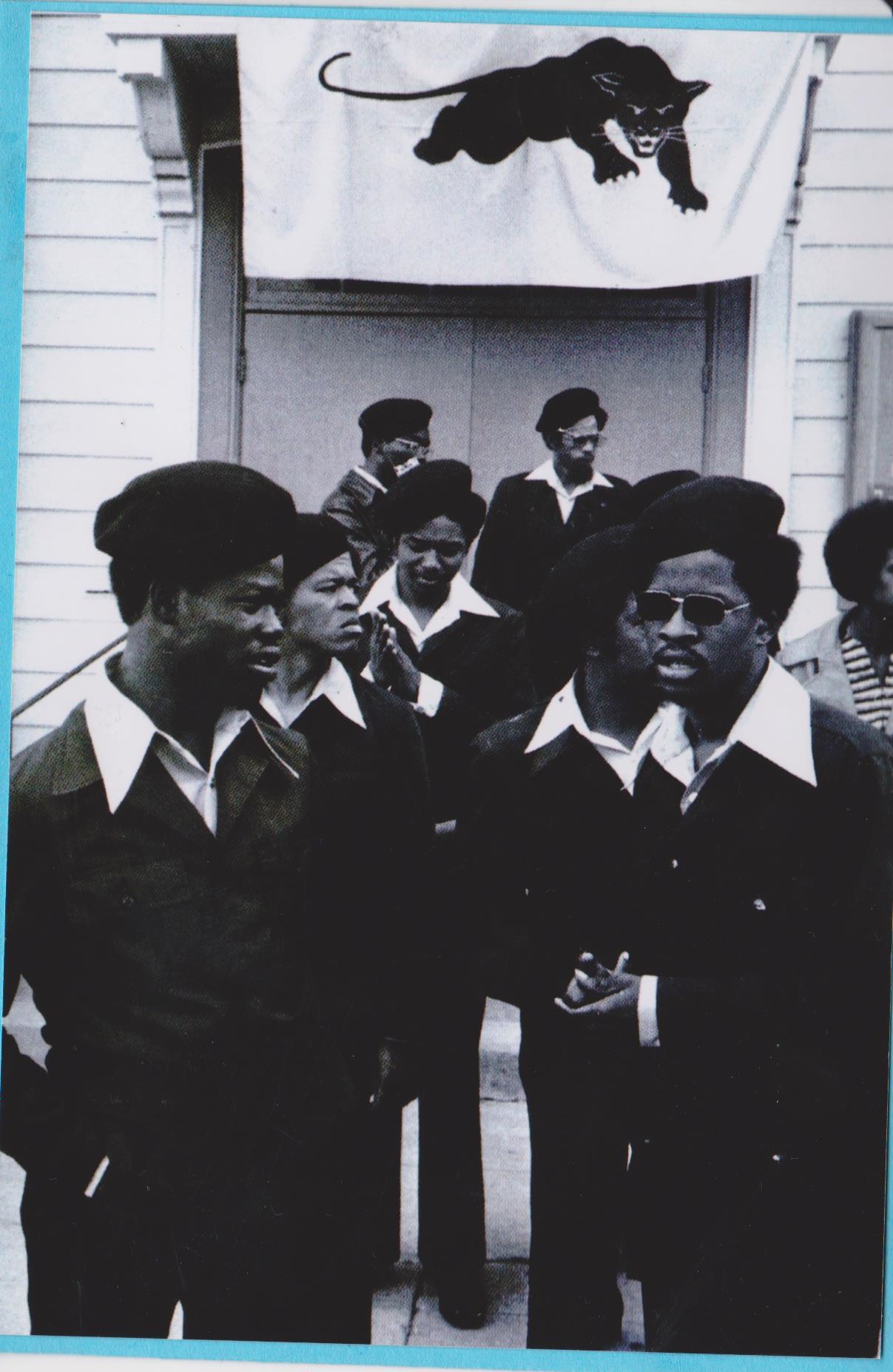

Editor’s Note: Bill Jennings, a Black Panther Party (BPP) activist in Richmond 45 years ago spoke to reporter Steve Early about the Panthers’ local origins and a new feature-length documentary called “The Black Panthers: Vanguard of the Revolution.” The film opens in Oakland, Berkeley, San Francisco, and San Rafael on Oct. 2.

Steve Early: As an archivist and historian for the BPP, you have long tried to set the record straight about its positive impact and accomplishments. Nearly fifty years after the Party’s founding in Oakland, how do you explain its “vanguard” role to young people today?

Bill Jennings: Well, to me, being in the vanguard means that you’re the group out front, the leader who is paving the way and setting an example. Even though we were very young ourselves, we showed people how to do things.

We provided a structure to help build the community and opportunities to give back. Many of the programs we started were later adopted by other institutions with far more resources.

SE: How did the Panthers get started in Richmond?

BJ: Six months after the Party was founded in Oakland [in 1966], there was a police shooting in North Richmond. The death of Denzil Dowell was covered, in depth, in the first issue of the Black Panther newspaper.

His family contacted Huey Newton and Bobby Seale, co-founders of the party, and asked for their help because they weren’t satisfied with the coroner’s report or the sheriff’s version of what happened.

The Panthers came to North Richmond to investigate Dowell’s death, which sparked a lot of organizing against police brutality. In April 1967, four hundred people, of all ages, attended a community rally. Many of them signed up to become members.

SE: The Panthers were well known nationally for their confrontations with the police. Yet, in Richmond, the party engaged in various forms of community service. Could you describe some of those programs?

BJ: We started a free breakfast program that fed 35 to 45 kids per day. We collected and distributed bags of groceries and gave away 2,500 free pairs of shoes. We did testing, door to door, for sickle cell anemia and hypertension. At the time, African-American history was just not taught in Contra Costa County public schools. So we started a “liberation school” that held classes on Saturday mornings.

In 1969, the whole community was badly flooded after heavy rains, leaving people stranded in their houses and on their porches. The plumbing was not very good and the sewage system would back up. So that added to the mess. We mobilized a 2-day operation, that Bobby Bowens, one of the Richmond Panther leaders was very involved in. Bobby and others put on tall boots and went in and rescued people. They distributed food to families in need and helped get others to the Red Cross evacuation center.

SE: Did the Panthers approach to the police change over time?

BJ: As we got more political education and understanding, we learned that there were other things we could do—like push for community control over the police, rather than just confront them. We demanded that the police live in the community and that there be sub-stations in the community, so people with problems and complaints didn’t have to go all the way downtown. We registered 1,500 voters so people could sign our petitions, vote on ballot measures, and get called for jury duty in places where there would otherwise just have been all-white juries.

SE: What did your Panther involvement mean to you personally?

I was just 20-years-old and living in Oakland in 1970 when I was transferred by the Party to work in Richmond. I had dropped out of Laney College because there was so much going on. There is no better feeling than knowing that you are doing something to change people’s lives. You wake up every morning feeling good about it.

For more on Bill Jennings archive of historical materials on the BPP and scheduled exhibitions of his collection or related Panther history talks, see:http://www.itsabouttimebpp.com/home/home.html or It’s About Time/BPPon Facebook.

For more on the BPP’s Richmond history, see Early’s forthcoming book, Shelter in Place: Reshaping Politics, Power, and Public Policy in a California Refinery Town (Beacon Press, 2016).

Sorry, the comment form is closed at this time.