08 Jul Q&A: The Re-Segregation of America

EDITOR’S NOTE: After Mitt Romney’s defeat in 2012, the Republican Party determined that it needed to connect with the nation’s increasingly diverse electorate. But two years earlier, writes author Dave Daley in his new bookRatf**ked (Liveright), GOP strategists had already embarked on a strategy to win control of Congress by in effect “re-segregating” America. The title for the book comes from a term used to describe political deeds done on the cheap to sabotage opponents. Project Redmap used redistricting to create gerrymandered districts in key states based on race and political preference. It’s “the oldest political trick in the book,” according to Daly, and one with political implications long after the upcoming 2016 race. Daley is editor in chief of Salon.com. This interview has been edited for clarity and length.

How much did you know about gerrymandering before starting this project?

I didn’t understand until I started in on this exactly how systematic and purposeful the Republican plan in 2010 was. I fundamentally didn’t understand how the Democrats could have the kind of year they had in 2012 – in which they win 25 of 33 Senate seats that were up, in which Barack Obama gets reelected with a big Electoral College majority – and the House only budges seven or eight seats, and the Republicans still have a 234-201 majority, and the House remains the center of Republican obstruction to the agenda of a democratically elected president.

As I looked at it, trying to figure out how this could happen, I learned, “Oh, the Democrats got 1.4 million more votes in 2012 for their House candidates than Republicans got.” And I’m like, “Well how is that possible?”

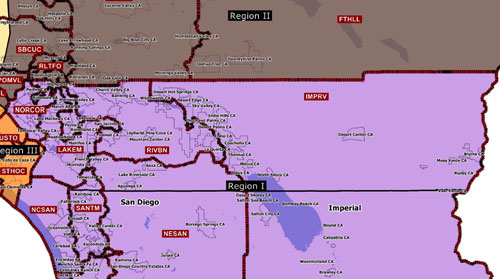

What has happened is that the lines have been drawn in such a way as to pack all the Democrats into as few seats as possible leaving Republicans to take the other votes for themselves. And they used the oldest tool in the book – the gerrymander – but they used it in a radical new way, in a very technologically savvy way, in a way that you couldn’t have done in the age of doing maps with parchment paper and pens.

What impact has this had on politics at the state level?

The transgender bathroom bill in North Carolina, 60 percent of the state is opposed to it, it’s pushed through by as gerrymandered a legislature as exists in the country, which does not represent North Carolinians. They have drawn the map in such a way as to allow a minority to govern the entire state.

And this happens in state after state. In Ohio, there are more votes at the statehouse level for Democrats in 2012 [but] Republicans win a supermajority 60-39 in the statehouse. There are more votes for Democratic candidates in Michigan at the statehouse level and it’s a huge majority for the Republicans. You don’t get those results without having lines that are drawn intentionally to disenfranchise people.

Look at the emergency manager bill in Flint. There is something that a gerrymandered Michigan legislature passes. The people of Michigan, who voted for Democratic candidates in the House, end up with a legislature that puts the emergency manager thing through. They have a referendum that overturns it, and the gerrymandered legislature then says, “No, we’re putting it back.” And that is the provision that allows them to replace the government in Flint with the folks who make the decision to reroute the water supply.

So people think of gerrymandering as the thing that put us to sleep in eighth grade civics class. It is the building block of everything. When you draw these lines, you have the power to create policy outcomes that are sometimes the exact opposite of what the majority wants.

How did mapmakers take into account the increasingly diverse landscape in these states?

There are two main ways you can do this. There’s packing and there’s cracking.

So, packing means trying to cram as many people as you can into one district. A good example of that is the Philadelphia district that elected Senator Chaka Fattah. He wins with the largest number of votes of anyone in the country – way over 300,000. Because they packed so many Democrats into that district, he wins at 80 percent. As a result, that allows all the other suburban districts to be bleached and more Republican.

Michigan’s 14th – which I drove every turn of – the goal there is to connect the poorest, most African American neighborhoods in Detroit with the city of Pontiac, which is about 35 miles north. In order to connect Pontiac and these neighborhoods in Detroit, you draw really insane, swerving lines that … candy swirl like a psychedelic lollypop on all of these sides. So the 14th District elects Brenda Lawrence at 78 percent of the vote. But Michigan also elects five or six Republicans in neighboring districts.

Cracking is the opposite. The one axis of the 14th District is 8 Mile Road, made famous by Eminem. And there’s one little cutout … that is the town of Farmington Hills – 10,200 people, white, suburban. It’s about a couple square miles, and they have intentionally vacuumed those Republican votes out to hand them to the neighboring district.

Are people in these communities aware of what’s been done?

I think there is a lot of frustration. I think people have begun to figure out that this is intentional and that in many ways it is the re-segregation of America. They are using race in these districts as a means to pack as many Democrats and African Americans into one district. It’s a gross abuse of what the Voting Rights Act intended.

What are some of the other outcomes of Redmap?

What these lines have done is that they have made it so that our elections are completely non-competitive at the House level. You now have something like 435 House seats that are non-competitive. And when you have non-competitive seats, the only election that matters is the party primary, and when the only election that matters is the party primary, you get a race to the extreme. Congressmen fear governing, they fear reaching out to the other side, because they know that the only way they will lose their seat is if they do their job and govern. That is the surest way to earn a primary challenge.

So it changes the tone and the tenor of our politics. It changes our ability to actually work together and get things done. This is not politics as usual. It is not necessarily a reflection of a divided country. Politics and partisanship have hardened, yes, but there are basic majorities that believe in climate change, who back sensible immigration reform, that are pro-choice, that have reasonable positions on gun control. We don’t have to as broken and dysfunctional as we are.

What is the significance for minority electorates?

If you’re looking at this as a question of African American representation in Congress, it soared in the early 1990s because of these minority-majority districts. You get a Congressional Black Caucus that grows to its largest size since Reconstruction. And you can understand why black voters in the South, frustrated with being probably the biggest part of the Democratic Party coalition there but always being told to stand in line behind a white Democrat, might get frustrated and how this would be an appealing play.

That said, the consequences are the Republicans take the majority in all these states and you have states like North Carolina and Georgia, Alabama etc. that had been electing large delegations of white Democrats and by the early 1990s they are electing white Republicans and a couple of black Democrats. So it gets complicated. It’s bad for the Democratic Party, but it’s certainly good for representation of African Americans in the Congress and the country.

What changes with this latest redistricting is that the technology advances to a point where it’s so easy to draw really precise lines that lock in the partisanship and also the ethnic nature of these districts. It was not as easy to do this in the 1990s. It becomes so easy to group people based on ethnicity and to pack as many of them as you can into these districts in such a way that I think is not empowering … it seems to me that the goal here is to re-segregate rather than to encourage representation. These new districts, where Republicans win, are whiter than the rest of America at a time when America is becoming less white.

What do you expect with the next Census in 2020?

After the 2020 Census the lines will again be redrawn. What we have to keep in mind is the lines are redrawn at the state level. So the system is locked up in many, many places. And for this to be undone, it has to be unlocked in many, many places. It’s not as simple as winning one election.

Voter turnout is key, but these maps are so tilted that there has to be a concerted effort to take back state legislative chambers. The brilliance of Redmap is that it went to the heart of how we redistrict. It went state by state and said, “Well, the people who have seats at the table in Pennsylvania are the governor, the house and the senate. So lets be sure we have the only three seats.”

So the Democrats, if they want fairer lines in Pennsylvania, have to start to think about how they flip chambers. Now, they have to flip the chambers on these tilted maps. If they don’t tilt the chambers, you will have the same people drawing lines in 2021 as did in 2011. They have to flip more than a dozen state legislative chambers in 2020 on tilted maps. And those are the races that matter most.

It makes 2016 feel irrelevant.

It almost does. We almost need not bother holding these elections until 2020, because the outcomes are not in doubt. Which is a sad, sorry condition.

No Comments