18 Jan Storybooks for Kids Offer Counter Narrative to the ‘Whitelash’

But there is another narrative emerging, one that points to a country ready and willing to embrace its diversity, and it’s coming from an unlikely place.

“In the last four years we have seen a societal change in attitudes toward a more diverse and inclusive culture,” says Celene Navarette, co-founder of LA Libreria, Los Angeles’ first and only bookstore dedicated entirely to children’s books in Spanish.

Navarette, a mother of two daughters aged 5 and 10, was born in Mexico and moved to the United States as an adult. In 2012, she launched LA Libreria with her business partner Chiara Arroyo after the pair attended a book fair at their kids’ school. Navarette says the lack of books that reflected Spanish language and culture then was “shocking.”

“In a city like Los Angeles, which has 5 million Spanish speakers,” she explains, “it was sad to see that we didn’t have access to the rich tradition of children’s literature that exists in Spanish.”

Today, in addition to the brick and mortar store, Navarette and Arroyo also operate an online store and travel to book fairs and events around the country promoting their collection of books, a cross section of language and culture from across Latin America and Spain.

Navarette says demand in California – which just ended a 20-year ban on bilingual education – and the nation has never been stronger.

“I can tell you that maybe 90 percent of the people who contact us are parents who want to bring this kind of resource to their schools,” she says, noting the response has been “overwhelming.”

Danielle Deane is one such parent. A mother of three originally from the Caribbean, Deane says that as a “new American,” she is hungry for stories that reflect the wider world.

She points to a long list of books that she reads to her own children, including “Of Thee I Sing, A Letter to my Daughters,” by President Barack Obama, and “A Tree Grows in the Bronx,” about Supreme Court Justice Sonya Sotomayor.

But Deane, who has considered starting her own children’s book publishing business, says diversity needs to extend beyond simply including characters of color, noting the narratives themselves need to reflect a broad array of experiences that move beyond the usual tropes.

“I don’t want my son to think that all the books with folks of color are just about slavery and strife or even about over achievers,” she explains, “but also about joy and everyday life … about gardening and family and flights of fancy and music.”

Picture books are often the first representations of the wider world we present to our kids. And there have been numerous studies pointing to the role children’s literature plays in helping kids prepare not just academically for school but also socially.

One study out of the University of Chicago found that the early years between 0 and 3 are when kids begin to develop not just cognitive functions but also notions of race and gender, and that these notions take root by ages 4 and 5.

“We know that kids notice these things from an early age,” says Rashmita Mistry with UCLA’s Graduate School of Education, adding that parents are often reluctant to acknowledge this fact. “Often the signals we give them is that … it’s ok to talk about colors of fruits and trees and animals, but it’s not ok to notice skin color. And that can be really confusing to young children.”

Mistry says its important for parents to not just read a book to their kids from “cover to cover,” but to use the stories as “jumping off points” to explore different features introduced, from kinds of foods, and colors, and people.

Doing so, she says, will “then translate into academics and the school readiness skills that we often talk about.”

But when it comes to diversity and children’s literature, there is more than just academic readiness at play. Writing for Mother Jones, journalist Dashka Slater notes that the issue gets at some of the most “pressing cultural questions of our time: Whose story gets told, and who gets to tell it?”

Current data suggests the answer to that question is, not too many.

Children’s publishing is a $2 billion industry. And yet, of the thousands of books published each year only a small fraction are reflective of communities of color, according to annual surveys by the Cooperative Children’s Book Center, part of the University of Wisconsin-Madison’s School of Education. Last year’s survey found that of 3,200 books published, just 14 percent were by or about people of color. The figure has changed little over the years.

That can be discouraging for aspiring authors who feel shut out by a publishing industry that, much like tech, is predominantly white and male.

But there is a growing movement in response, including one young 11-year-old who launched a social media campaign last year called #1000BlackGirlBooks. There is also the non-profit We Need Diverse Books, which launched its own social media call in support of greater diversity in children’s literature.

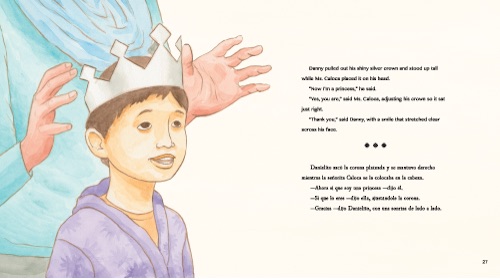

There are also a growing number of independent publishers, including Oakland-based Blood Orange Press, which last year published “One of a Kind, Like Me/Único como yo” about a multiracial four-year-old boy who tells his mom that he wants to go to the school parade dressed as a princess.

Author Laurin Mayeno says the book is based on her own experience with her now-grown son.

Mayeno, who is the founding director of Out Proud Families, which works to educate parents and caregivers about gender identity and expression in young children, says that at the time there were no stories that she could turn to that reflected her experience.

“Back then, I … felt very alone,” she wrote in an article for Huffington Post. “I was confused and scared. I wasn’t 100 percent accepting of how Danny expressed himself, much less proud. I’ve learned a lot since then.”

Mayeno says she hopes her book serves as a resource for families like hers, adding that in readings to pre-school kids around the country the story has proven to be a useful tool to broach the subject of gender identity.

“A lot of the kids would ask, ‘Why does he want to wear a dress?’ Once I explained it to them they accepted it a moved on. They stopped seeing it as unusual,” said Mayeno.

For Navarette, despite the election outcome the current narrative around the country is indeed one of diversity and inclusion.

“We are raising global citizens, people who will travel for business and will be able to communicate and will be sensitive to cultural differences in all these countries,” she says.

Parents increasingly want the tools to help them prepare their kids for that world. “It’s very powerful and I don’t see a change in that.”

No Comments