17 Jan Remembering the Original 21ers: a Q&A with Jake Sloan

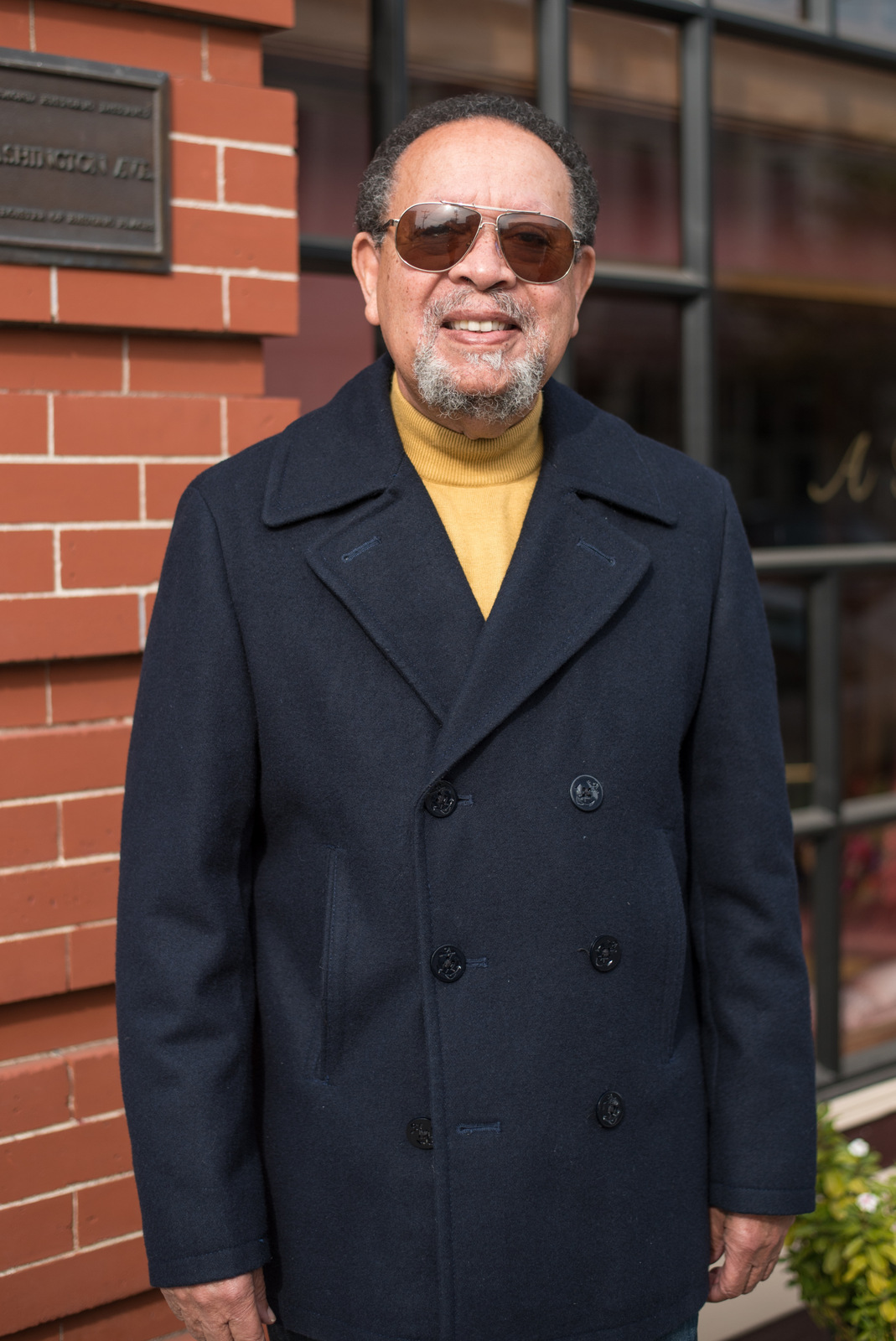

Interview, Malcolm Marshall | Photo, David Meza

Editor’s Note: Richmond resident and author Jake Sloan was a member of the Original 21ers, a small group of African-American workers at Mare Island Shipyard in Vallejo that, in 1961, signed and filed a complaint of discrimination with the U.S. government. One-third of the men who signed the complaint were from Richmond.

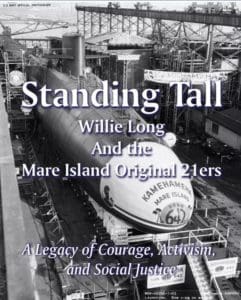

Sloan has authored a new book, Standing Tall: Willie Long and the Mare Island Original 21ers, that examines discrimination and inequality, including hiring opportunities, pay, and general job security, at Mare Island Shipyard from the 1930’s up until the action was taken in 1961.

The CC Pulse sat down with Sloan to discuss his book, his time living in Richmond, and what it means to stand tall.

The CC Pulse: What inspired you to write Standing Tall?

Jake Sloan: I first thought seriously about it in 1980, but I got serious again about it about 15 years ago. I knew it was important. I wanted the leaders in the organization to get some recognition.

Secrecy was of such importance that we didn’t talk with anyone about it. Probably only one family member out of all of us knew anything about it. So, I thought it was important for the story to be told, not only for the family members, but for the African American community because it had tremendous and pretty widespread impacts over the years.

RP: Who was Willie Long?

JS: Willie’s father worked for [former Oakland Raider great] George Atkinson’s grandfather as, as a laborer. Willie served in the Navy during World War II. He worked in various shipyards around the country, and finally wound up at Mare. Willie was a very conscientious person, who believed in excellence in everything. He became an apprentice at Mare Island, graduated from the apprenticeship program around 1950, and became an outstanding pipefitter, but could never get a promotion to supervisor, just as John Edmondson couldn’t. John had been there for 30 years and was considered to be the best pipefitter on the yard, but couldn’t get promotions. Willie was a guy who just wouldn’t accept that. He decided in 1960 to organize. He was a great man.

RP: What was it like for you working at the Mare Island Shipyard from 1960 – 1964?

JS: If you were an African American man at the time, it was probably the best job you could get. If you were working in the trade, it was good job because you had, especially if you were a veteran as I was, you had job security. You had benefits. But, if you were allowed to work in the building trades, you couldn’t get into the union outside of government work. It was virtually impossible.

I was a pipefitter, plumber, and we installed all the pipes in the nuclear submarine. I worked mainly in the reactor, installing the pipe. I looked around at guys that I respected who had been there for 15 or 20 years, and couldn’t get a promotion. And when we had the opportunity, under the leadership of Willie Long, to do something about it, I was ready.

RP: Willie Long was influenced by the Freedom Riders, and others things that were happening with Civil Rights Movement in the South. What was going on that led Long and the rest of you to take this kind of risk?

JS: We put our jobs on the line. There was no doubt about that. It was about the height of the Civil Rights movement and we were reading about the things that were happening in the South to our people. Willie Long said something to the effect that, If those people can put their lives on the line for change, I can put this little job on the line.’

And then, President Kennedy established a committee to address discrimination in hiring and promotions in the Federal Government. Willie read about it and decided that we should take action.

Willie had been thinking about taking action for 10 years or more. And other African-Americans before had tried to take action, including his great mentor, John Edmonson. But the guys would decide they were going to take action and then, at the last minute, everyone would back out and John Edmonson would be standing alone.

Willie just made a decision that he was going to do something about it and when the President set up the committee, he decided that we would file a complaint of discrimination to the Federal Government.

RP: What was the result of the complaint?

JS: There were two sides to the result. First, the leadership at Mare Island never admitted that there was discrimination all the years after that. When the Federal Government sent out a team to study the issue, they never officially found discrimination.

But, things began to change almost immediately on the shipyard. They looked at different ways of addressing promotions for everyone, including African-Americans. And some of the men who signed the complaint got fairly significant promotions, some almost immediately, and some over the years for sure got some very significant promotions.

In many cases, the men who were opposed to us taking action — other African-Americans workers — some of them got the best promotions over the years. There were more than 1,000 African American men working on the shipyard at the time and we could only get 25 to sign. But of the guys that, that signed the complaint, all got promotions, except Willie Long. He got a temporary promotion but nothing permanent.

But there was never an admission of discrimination either on the part of the leadership at Mare Island, or the Navy.

RP: At that point did you all feel that the risk was worth it?

JS: We did. It was worth the risk and many of the guys benefitted greatly. One of the side effects was that we formed a great brotherhood. We were all dedicated to each other, right up to today. And so, it was a great experience because it showed us what can happen if you’re willing and have enough nerve to take action. That’s the reason I entitled the book Standing Tall. We learned, beyond a doubt that if you’re going to make change, you have to stand up to it.

I interviewed all the guys who were surviving when I really got into the book. And none of them thought that there would be significant change, or would have been significant change if we hadn’t taken the action.

RP: How did it change you personally?

JS: I was not a leader in the group. I was a role player, foot soldier, but I was dedicated to the cause, and I’m glad I participated.

I saw first-hand the need to always stand up for what you believe in and to be willing to take action and some risk. Now, although I didn’t take risks, all the others did, I just saw that that was what was required to, to make any change. And also, the guys were all mentors of mine in one way or the other. And a few of them encouraged me to get an education because, at the time, I was a high school dropout with a 10th grade education on paper, and probably sixth-grade in reality. They encouraged me to leave the shipyard and get an education, which I did. And so, that changed my life fairly dramatically.

Also, since then, I have always worked either as an employee, or in my own business in an effort to change the complexion, so to speak, of the construction industry. And that’s been my profession and my business since then. I feel in many ways that I owe everything that I’ve been able to accomplish in life in some way to those guys.

RP: When did you first come to Richmond and what brought you here?

JS: My family came to Richmond in 1948. What originally brought us here was the same thing that brought most people during that period: economic opportunity and jobs. My father had come out several times seeking employment, and once he was fairly established here, he sent for the family. We all came out, and the family lived in North Richmond, which was then and now, a pretty tough place, but it was a pretty close community.

I joined the Army when I was 15 because I was bored. When I came from the Army, I was fortunate enough to get a job at Mare Island, and as they say, the rest is history.

RP: What was the cultural mix of North Richmond like for Black folks at that time?

JS: We got along, because it was basically a Black community. We didn’t really have a lot of in-your-face discrimination, but it was clear that we were separate, and definitely were treated differently by the police.

Many of the African Americans wanted to get out of North Richmond, but you held there, because of economic realities, but most, as soon as they got a chance, moved out. The people who wanted to succeed, for lack of a better way to put it, would leave as soon as they could

North Richmond was a close community. Everyone knew everyone else, we all grew up together. We fought often, but when the fights were over, we were one big family.

RP: What would you like young people to get from your book?

JS: I think it’s important, especially to the people in the Bay Area, because at one time, just about every African-American was either directly or indirectly connected to someone who was working in the shipyards at the time, 21ers and others. And so, it, it’s a part of our history. A young person probably had a great-uncle, or a great-grandfather working at Mare Island, or Hunter’s Point, or one of the other Military installations.

It’s important for us to know that history, but the bottom line is I believe that we need to tell our story. That’s a story that should be known. If we don’t tell the stories, someone else will, and they won’t tell them from our perspective.

This interview has been edited for clarity.

No Comments