17 Sep Lawyer Alleges Citywide Voting in Richmond is Racially Unfair

By Edward Booth

A Walnut Creek attorney has accused the city of Richmond of having a voting system that results in racially biased voting.

In a 32-page letter sent to the city Sept. 11, Scott Rafferty alleges the city’s at-large voting system, in which councilmembers are elected by citywide popular vote, dilutes the Latino vote, violating the California Voting Rights Act of 2001. Rafferty says the city must move to a district-based system, with candidates elected from separate areas, or face a lawsuit.

“Neighborhood-based elections will give every Richmond voter, regardless of race, the opportunity to vote for the candidate who will be most effective in representing the values and interests of their specific community,” Rafferty wrote.

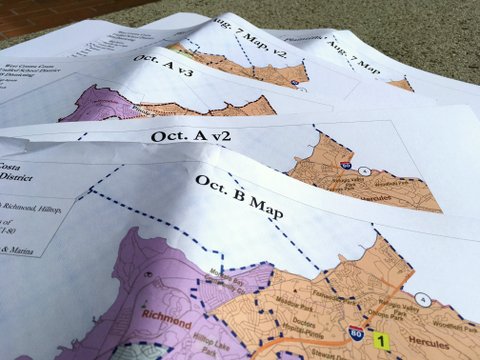

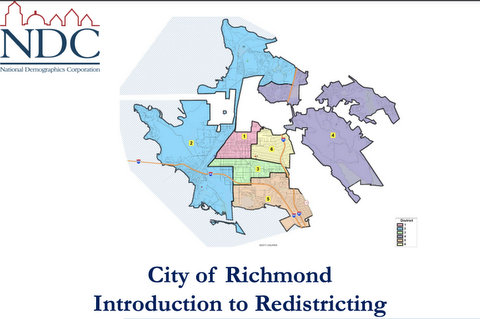

If a city does not establish intent to change, the attorney can file a lawsuit, in an attempt to force a switch. If the switch is made, either voluntarily or forced by a lawsuit, the city would then need to gather community input at five public hearings and hire a demographer to draw district maps within 90 days.

The California Voting Rights Act lowered the level of proof required for minority groups to show that at-large elections weaken their voting power, creating an increasingly common scenario statewide: Letters sent by lawyers, or the threat of them, have prompted hundreds of cities and school districts to change their voting systems. Some did so voluntarily. Others tried to fight the demand, but none have yet beaten a CVRA lawsuit, with some shelling out millions of dollars in the long run.

Under state law, if a city or school district concedes to a demand letter, it must pay the lawyer who drafted the demand $30,000 as reimbursement for demographic studies and other effort put into writing the letter.

Rafferty has initiated several of these legal actions in recent years, including one that led to the West Contra Costa Unified School District settling a lawsuit and paying $310,000 to Rafferty in attorneys fees.

Richmond Mayor Tom Butt said he was surprised that the city had received the letter given the historic diversity of the city council. He said African Americans are currently overrepresented on the council; while two to three years ago, Latinos were overrepresented.

“Year in and year out, Richmond has had a very diverse city council, and unlike some other bodies, it’s pretty hard to make a case that there are unrepresented bodies in Richmond,” Butt said. “I mean, the only unrepresented people right now are females and district elections are not going to fix that.”

Richmond resident Don Gosney, who opposed Rafferty’s actions at West Contra Costa school board meetings, argued against the switch. He said that, unlike with the school board, the city could hand over a list of councilmembers, going back decades, to demonstrate diversity.

Gosney also argued that forcing the city to switch before the 2020 census is a bad idea. Because the district-areas must legally be drawn with the latest census population data, Gosney argued, they would not represent the actual population and would have to be revised.

“This guy is not interested in taking care of the different ethnicities, making sure they’re represented in Richmond,” Gosney said. “It’s payday for him. He gets $30,000 just for sending the letter.”

Rafferty said that going forward with the switch would make the map a good “rough draft of something that could last for 10 years.” He added that because demand for demographers will be heightened after the census, developing a map now allows for an easier transition later.

As for the benefits of district elections, Rafferty argued they would increase voter turnout of minority groups, make elections less expensive to run and reduce influence from special-interest groups.

“A neighborhood election is more likely to depend on how effectively you communicate … than whether you’re on the Chevron slate or not,” Rafferty said.

Cesar Zepeda, president of the Hilltop District Neighborhood Council and two-time city council candidate, has long supported district elections and helped organize efforts to add district elections to the ballot before his first campaign in 2016.

He argued a shift would not only improve diversity but also expand the areas elected officials have a personal stake in. Hilltop, he said, hasn’t had a councilmember in decades, while Point Richmond and the Marina Bay area have historically been overrepresented.

This, Zepeda argued, would increase accountability and help the entire city feel politically connected. This connectedness would be further enhanced, he said, by the significantly lower cost of focusing a campaign in a specific portion of the city, which he said could open the door to qualified candidates who otherwise would have been financially locked out of running, or who would have relied on special-interest funding.

Some argue that district elections would only deepen divisions, including one councilmember whom Zepeda recalled saying they represented the entire city, not just the area in which they lived. Zepeda argues it’s not so simple. “That is the right political answer; as a councilmember, you have to represent everybody,” he said. “But [if] you don’t live in the same area [as] your constituents, you don’t see the trash, you don’t see the potholes, you don’t see the needs.”

The City of Richmond has 45 days, from receipt of the letter, to show it intends to amend the city’s voting system, or risk getting sued.

Bill

Posted at 23:19h, 19 SeptemberHow many of the candidates and city officials are from Point Richmond? Most of them are and have been. PT. Richmond is the white mafia of Richmond

Yes, zone them!