11 May How California Community College Foundations Are Trying to Help Students

Above: A student walks back to her car after picking up eggs, milk, produce and dried goods from the weekly drive-thru food pantry at Santa Monica College. Photo by Mikhail Zinshteyn.

By Mikhail Zinshteyn, CalMatters

In the third week of April, Shannon Hill approved the donation of some $35,000 in emergency aid to 40 students at Cuesta College in San Luis Obispo.

Hill, the executive director of the Cuesta College Foundation, the nonprofit arm of the community college, said that in a normal school year the foundation doles out $90,000 to $100,000 in aid. But given the economic toll the pandemic has taken on students, especially the many community college students who work part-time, the foundation is aiming to distribute closer to $250,000 this year.

It’s joining other local community college foundations that have been raising money or redirecting existing funds to help plug the gap that remains after state and federal aid.

At Cuesta, that means prioritizing undocumented students and others who were barred from receiving a portion of the federal stimulus money colleges and universities are set to receive through the federal CARES Act for pandemic relief that Congress approved in March. The stimulus dedicated $14 billion to higher education in the U.S. Of that, California’s higher-education sector is supposed to get at least $1.7 billion.

“We do anticipate that more of our emergency grants will likely go to students who are not getting the CARES money, because we’ll be helping to fill that gap for our students,” Hill said in an interview late April, whose foundation is giving out grants of $1,000 to students and another $500 for students needing a second installment.

Money with strings

The country’s higher-education community cried foul when the U.S. Department of Education said in late April that the roughly $6.3 billion meant for direct student aid was off-limits to certain students, such as those who had defaulted on past federal loans, had below a C average, have certain drug convictions and are undocumented. One estimate is that there are 454,000 undocumented college students in the U.S., and a fifth live in California.

Democrats in the House and Senate wrote separate letters to Education Secretary Betsy DeVos saying that restrictions imposed by her department went against the spirit of the legislation.

And all that federal money isn’t enough to replenish the college budgets hampered by the pandemic or the aid students need. The Legislative Analyst’s Office warned in an April report that “initial data suggest that the federal relief funding provided under the CARES Act likely will be insufficient to address the full effects of the outbreak.”

Local philanthropy can help to close the gap. The vast majority of California community colleges have an associated foundation, like the one at Cuesta. Several foundation directors say they’re using their available dollars to support undocumented students, along with other students in need. The faucet of foundation cash turned on just as destabilization wrought by the COVID-19 pandemic became more apparent. The foundations responded to a wide range of student needs, such as food distribution, laptops or other mobile learning tools and emergency grants to cover rent. These efforts indirectly support students who wouldn’t qualify for CARES Act funding, foundation heads say.

“We have many, many students who would not receive any support from the CARES Act but will receive our scholarship funds,” said Lizzy Moore, president of the Santa Monica College Foundation. It raised $780,000 in scholarships to mete out to students, a banner year, Moore said.

The foundation also partnered with Los Angeles-based meal-delivery company EveryTable to send seven free meals weekly to 1,000 students, which works out to $44 spent per student a week, Moore said. By late April, she had raised $1.25 million in five weeks for the meal program, enough to keep it running through early September while feeding 1,500 students. It’s a service the foundation created toward the end of March after realizing students who relied on the college’s food pantries would be cut off from food as shelter-in-place orders closed campuses and pushed college instruction online. Anywhere from 100 to 200 students used the school’s pantries before the pandemic. Students are eligible for the meal-delivery program if they’re referred to the program by faculty or staff. In a nod to safeguard student privacy, recipients of the meal program don’t have to put down their actual names to receive the meals, Moore said. They could also request to send the meals to another address and pick up the shipment there.

Food for thought

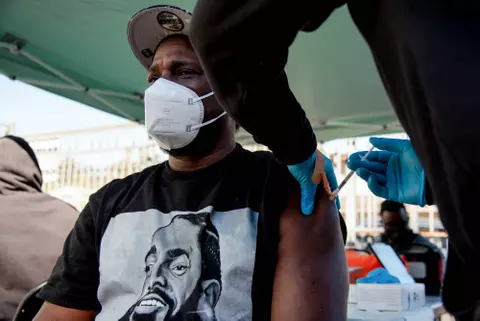

The foundation also began running a weekly drive-thru food pantry to help students through the pandemic. On Wednesday, the pantry fed 289 students, who received a bag of fresh produce and shelf-stable food along with 18 eggs and milk. For eligibility, students just need to show they’re currently enrolled at the college.

“I don’t have to … risk to go out and buy food and second of all I don’t even have that money, so getting the food from school has been a blessing for me and my child,” said a student of the college who’s undocumented and requested anonymity. Through the foundation, she’s received the meal delivery plan and food from the pantry. The food alone saves her $150 to $200 a month, she said.

The immigrant from Cameroon works part-time as a homecare assistant. It’s just enough to cover her rent, but her priority is attending school full-time. Between her own school work, classes and assisting her daughter with her own lessons, “it’s heavy,” she said. Sometimes she brings her laptop, provided by the college, to work. When a patient sleeps, she opens her computer to keep up with classes.

And though she’s ineligible for federal financial aid, California’s financial aid programs are open to undocumented student residents. Her tuition is waived and she receives several state grants, including about $3,000 a semester for being a student with a child and $649 for attending school full-time.

“I just have no words, to be honest,” she said. “I just feel like I’ve been surrounded with good people.”

International students gain from the foundation’s efforts as well. Skander Zmerli came from Tunisia and studies at the college, where he’s a member of the student government. He receives free meals through the foundation’s EveryTable program. The college, he said, is compensating for “the fact that the federal government isn’t giving any financial support to international students.”

College foundations are limited in how much of their assets can go directly to students’ emergency aid. Because donor money has to be spent how donors want, foundations don’t have as much flexibility to change money allocation on the fly. At Chaffey College Foundation, which supports the Inland Empire community college, 93 percent of the foundation’s funds are restricted to scholarships and program support, said its executive director, Lisa Nashua.

Almost all of the Foothill-De Anza Foundation’s $40 million in assets are restricted. Still, the foundation, which supports the Bay Area colleges Foothill College and De Anza College, freed up more around $350,000 in discretionary funds for the colleges to use in response to the pandemic, said Dennis Cima, executive director of the foundation. It’s using the money as a stop gap until federal CARES Act money reaches students and for students who wouldn’t be eligible for the federal relief anyway.

The foundation has about $1.25 million in discretionary funds remaining, but it won’t use it all this school year. Cima said the foundation needs to anticipate the emergency aid support of students in the next school, especially if the economy continues to slide and more workers unable to find jobs head to community college to acquire new skills and request extra financial help.

In past years the foundation spent $25,000 to $50,000 from its discretionary pot, typically paying for end-of-year college events, student scholarships, supporting abroad studies trips, food pantries and other expenses. With shelter-in-place orders, those activities are unlikely to happen soon anyway.

By spending more now, the foundation will have less on hand once it’s safe for students to head back to campus. Cima will attempt to fund-raise more to refill the discretionary pool, but drawing down the money now to address an unprecedented need is the foundation’s role. “I am comfortable allocating these discretionary funds knowing the immediate need that our colleges and students have,” Cima said.

Formula mismatch

California community colleges enroll nearly 60 percent of the state’s college students but will only receive a third of the main federal funding made available to the state’s institutions of higher learning, according to the April report by the Legislative Analyst’s Office. Nationally, community colleges received less funding per student than did all other types of colleges, including public universities and for-profit colleges, according to a report by The Century Foundation.

The reason for the mismatch is because the CARES Act counted the number of “full-time equivalent” students instead of the number of enrolled students, a formula which “absolutely disadvantaged community colleges where significant shares of students are part-time,” said Debbie Cochrane, executive vice president at The Institute for College Access & Success. “For community college students, it really adds insult to injury.”

Community college students often can’t afford to attend classes full-time and need to work as well. As a result, using course units to determine relief money has different real life impacts for part-time students. One way to visualize this, Cochrane said, is to imagine two part-time students who now need laptops at home because classes moved online In that scenario, the logic of full-time equivalency falls apart. “Two part-time students can’t share one laptop. Two part-time students need two laptops,” Cochrane said.

All funds on deck

Beyond foundations, community colleges could access state funds to support students facing financial emergencies, including ones ineligible for federal financial aid. A state law passed last year allows community colleges to tap into a nearly $500 million annual pot originally intended for student advising and other academic support to also be used for student emergency aid.

Because the state law went into effect this year, it’s unclear how many colleges are using the funds — the Student Equity and Achievement Program — for emergency aid purposes. Assemblyman David Chiu, a San Francisco Democrat and author of the law allowing the money to go to student emergency aid, said in a statement that the emergency aid dollars could offer relief where the federal government does not.

“I hope that emergency grants will be a useful tool to support our community college students at a time when so many are struggling,” said Chiu. “Given that Secretary DeVos is using the COVID-19 crisis to play politics at the expense of our undocumented students, state-based emergency grants may give us an opportunity to step in and help these students.”

Despite the dire state fiscal situation, there are still ongoing efforts to send more money to students most affected by the escalating recession. The state community college system and the agency that oversees the main financial aid program is asking Gov. Gavin Newsom to send $500 in the upcoming school year to 82,000 low-income students, including nearly 12,000 undocumented students.

The University of California and California State University pledged to use internal resources to offer emergency aid support for undocumented students. A UC spokesperson did note that “the aid an undocumented student receives will be equivalent to the amount that an equally needy student who qualifies for CARES Act funding would receive.” The dollars come from flexibility the state has been giving the UC since 2013 to provide financial aid to undocumented students. A spokesperson for the CSU said its emergency aid for undocumented students at individual campuses “could come from a variety of sources including institutional funds, privately raised dollars, and foundation grants,” among others.

Fundraising during the pandemic is hard, some community college foundation directors said. Not only are benefactors being asked to support multiple nonprofits, but the shelter-in-place orders undermine the interpersonal touch that’s useful in highlighting to a potential donor a college program in need of philanthropic support.

“It’s hard to have a relationship with somebody that you can’t bring on the campus, you can’t visit them, you can’t have them see a program in action,” said Cima.

CalMatters.org is a nonprofit, nonpartisan media venture explaining California policies and politics

No Comments