06 Jun A Portrait of California Protests: Same Message, Different Motives

All protests, like politics, are local. Protesters are united in fighting racism but they have their own unique issues with their police force and city.

Nathaniel Johnson walked past a CVS pharmacy in Hollywood with his phone camera trained on men running out of the looted store with armfuls of stolen goods.

After a Minneapolis police officer killed George Floyd, Johnson had protested police brutality for two days while dressed in civilian clothes. But that afternoon, he decided to change into the uniform he wore for five years — his Army fatigues.

“Get out of the CVS, you’re criminals,” shouted Farrah Abraham in a 57-second video posted to Instagram. ”Get out of CVS!”

She turned her camera to Johnson. “This guy in the Army uniform is literally with them,” she shouted. She later took credit for sending 20 people to jail with her video, adding “I’m blessed there’s people like me on this earth.”

But Johnson, 30, wasn’t looting. He was recording both the thieves and the police who raced to the scene on Monday afternoon. His goal: show the police response while distinguishing between peaceful protests and the kind of destruction and theft that was taking place across the country.

Although he was a toddler in Los Angeles during the Rodney King riots in 1992, Johnson said the city’s long history of racial injustices and uprisings is leading to police and observers painting all black people with the same broad brush.

“We’re looters, rioters, criminals to them,” said Johnson, 30, an Army combat engineer and mechanic who was stationed overseas in Germany.

In other words, Johnson said he faces the same kind of fear and endemic racism that led to Floyd’s death and the protests in the first place.

The incident provides a unique snapshot of a protest and civil unrest in Los Angeles: A celebrity influencer in an expensive Hollywood apartment, yelling at people, all black, some guilty of vandalism and burglary, some innocent — 28 years after the deadliest riots in modern U.S. history.

The imagery of this week’s protests in Los Angeles — buildings burning against a night sky, people running and screaming, cars on fire — evoked memories of the 1992 riots, in which 63 people died. But the worries and hopes and raw fury of Californians who took to the streets this week show that all protests, like politics, are local. Throughout the state, protesters had their own motivations, their own methods, their own issues with their police force and their city.

In Merced, protesters asked why the north side of town remains wealthy and safe, while the south side wilts. In Sacramento, protesters demanded the firing of police officers who fatally shot a black man in 2018 in his grandmother’s backyard while he was holding a cell phone. And in Salinas, a police department three years into its own reforms is gleaning modest praise as well as complaints.

Uniting all the protests throughout California, as well as the rest of the nation, is the idea that police must reform — or be forced to reform — treatment of black people, from those shot by officers to those pulled over while driving.

Examining the motives of a protester in four different cities provides a snapshot of the personal experiences that are driving thousands of Californians to the streets this week.

In Merced: ‘Politics has to happen at home’

Merced isn’t really a protest town. The usual demonstration will draw maybe 100 people. But last weekend, nearly 400 people of all races showed up. What’s changed? Protesters said the combination of the toll the pandemic is taking on people of color, the battles over immigration and the killing of Floyd brought them out.

“I think the last four years caused that difference,” said Katrina Ruiz, who is in her 30s and lives nearby in Los Banos. “We have a president whose rhetoric perpetuates stereotypes against people of color. We have this pandemic, and the response to the pandemic was atrocious. It has gotten increasingly worse to be a black person in the last four years because of who we have in office. People are just outraged and they don’t know what to do.”

Locally, the city is divided along class and racial lines, Ruiz said. In north Merced, there’s investment, a new high school, grocery stores, easy public transit.

“You go to south Merced [and] there’s no grocery stores. There’s no sidewalks. The schools are heavily policed and there’s no investment in the community,” Ruiz said. “There’s investment in law enforcement.”

South Merced has a majority of people of color, with blocs of Latinos, black people and Hmong. The Merced County Sheriff’s Office has drawn the ire of activists over its cooperation with U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement.

“We have a department sheriff that, one, won’t speak to people in ICE custody, who says the sheriff’s department doesn’t cooperate with Homeland Security,” Ruiz said, “but there’s records to prove otherwise.

“I think this is a call to action for local and national leaders,” she said, “because politics has to happen at home.”

A day later and 56 miles southeast, Shannah Albrecht, a 24-year-old student at Fresno City College, said the 3,000-person assembly in Fresno on Saturday was her first protest.

“It was so diverse,” she said. “There were white people, Asian people, Hispanic people. There were people of all different ages. Everybody was there to support the black community and show they have allies, that everybody’s there for the same purpose, to show that they have people out there that do care and want all this to stop.

“It’s me finally getting to the point where enough is enough.”

In Sacramento: The specter of a shooting

Sacramento was the focal point of marches and protests in the summer of 2018, when two police officers shot and killed Stephon Clark, 22, as a Sacramento County Sheriff’s Department helicopter hovered overhead, recording the incident. The officers fired 20 rounds and later said they believed Clark had a gun. It was a cell phone. An autopsy found that three of the seven rounds that struck Clark hit him in the back.

The specter of Clark’s death hung over the protests in Sacramento this week.

“People are mad and rioting and looting, rightfully so, because they’re angry,” said Thongxy Phansopha, who attended vigils for Floyd and ferried supplies to protesters last week. “They haven’t been given the proper space to grieve.”

Officers who have killed or injured Sacramento residents need to be held accountable, said Phansopha, including those who fatally shot Clark. But that’s not enough. “Reforms are great short-term,” Phansopha said, “but it’s not the way for the future.”

Phansopha, who uses gender-neutral pronouns, didn’t know that they would become a victim, too, when they headed last Saturday to the capitol’s Midtown district to deliver a final round of snacks and water to friends protesting there.

As Phansopha turned a corner on foot, a chaotic scene awaited. Officers on one side of the street fired flash grenades and rubber bullets at protesters on the other side. Tear gas hung in the air.

Phansopha said they paused for a moment to inspect an empty tear gas canister on the ground. Suddenly, Phansopha felt an object collide with their head — another canister. Blood poured from Phansopha’s face and they collapsed slowly to the ground, started to crawl away and was swept to safety by other protestors. Phansopha said officers continued to shoot rubber bullets.

In the emergency room, Phansopha discovered the extent of damage: seven rubber bullets struck their face, neck, arm, shoulder, back and hip, leaving a bloody gash above their eyebrow, a fractured cheek bone and three skull fractures.

In the long term, Phansopha said activists should try to change how city money is spent and who decides how to spend it. In addition to fewer police officers, Phansopha said less money should go to the county jail, and those dollars should be spent on community-led alternatives, along with mental health services.

How that money is spent should be up to the community to decide, with “really big investments into the neighborhoods that really need it.”

In Salinas: Already rebuilding trust

At the rodeo grounds in Salinas on Monday evening, Selena Wells, a 24-year-old black and Mexican woman, stood quiet witness in the back of the crowd. She was there supporting her sister, a poet who read some of her work at the start of the protest and her mother, who would speak later.

Even though her mother isn’t black, she raised Wells and her sister with the knowledge of what it is like to be black in America, Wells said. She taught them they will be discriminated against because of the color of their skin, that they had to hold themselves differently in certain cases, to be more careful if they were pulled over by the police, and so on, Wells said.

She called for accountability for city police in particular.

“To be discriminated against based on the color of our skin, it’s wrong, it shouldn’t ever happen,” she said.

Salinas has a fraught history with police, which the department has worked to turn around in the last six years. After four residents were fatally shot by officers in 2014, tensions sparked between police and residents of East Salinas, setting off widespread protests.

A 2015 review by the Department of Justice found troubling deficiencies in how Salinas police worked with people with mental illness, used force and built community trust and engagement.

In response, under Salinas Police Chief Adele Fresé, the department has focused on hiring women and people of color as officers, as well as hiring people from the community. The Salinas Police Department also revamped its approach to training, emphasizing de-escalation and community outreach.

The county District Attorney’s Office began an independent review process of every officer-involved-shooting, a significant milestone for activists.

At Monday’s rally, Fresé said she believed the steps the department had taken in recent years to emphasize trust and community-building between law enforcement and civilians was essential.

Still, memories are long, and relationships between the community and police remain frayed in Salinas.

Fresé faced some brief heckling Monday night, when, during her remarks, a handful of protesters called for justice for Brenda Rodriguez, a new mother who was shot and killed by Salinas police in March 2019 after an eight-hour standoff with officers who responded to a domestic violence call at her boyfriend’s mother’s house.

Rodriguez was shot after she “pointed a realistic-looking airsoft pistol directly at” officers, said Monterey County Managing Deputy District Attorney Christopher Knight at the time.

Local activist organizations held protests in Rodriguez’s name in the following months.

The officers involved in the shooting death were found to have acted appropriately by the Monterey County DA.

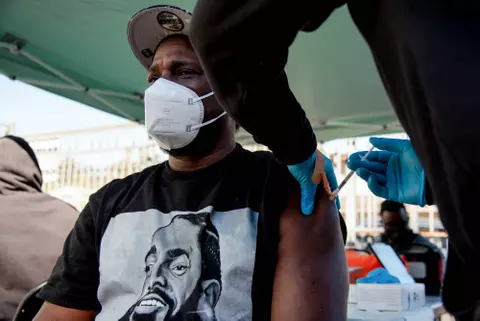

In Los Angeles: A military presence

Johnson hoped the power of his uniform might protect him on Monday. Last Saturday and Sunday nights, when Johnson dressed in regular clothing, “I came out as a civilian, a protester, and I was met with tear gas, I was met with batons, I was met with violence,” he said. “They just saw us as criminals and thugs. I felt like I was in a war.”

So he came out Monday in fatigues.

“I approached [the police and National Guard] with my military ID and my dog tags. They’re the same people I was when I was serving. I’m a soldier. It never goes out of you.”

But he said it didn’t make a difference. The protest on Monday in Hollywood ended the same way: tear gas, threats of rubber bullets and arrests.

One of Johnson’s chief complaints was the use of the National Guard to quell protests, along with President Trump’s threat to send the military onto American streets.

“Having been trained like them, I’m a soldier, the kind of torture they put you through in the military is to make you say, I can do it, I can kill,” Johnson said. “And when they get out, what jobs do we give them? Police.”

The use of tear gas and rubber bullets has drawn the ire of civil liberties advocates. But in protest after protest during the unending week of unrest in Los Angeles, police in full suits of body armor, face shields and military hardware act as crowd control long before the shooting starts.

Protests are, ultimately, a negotiation between those protesting and the government they’re seeking to reform. Los Angeles Mayor Eric Garcetti had proposed an increase to the LAPD in his 2020 budget proposal. Then Floyd was killed and the protests began, many of them focusing on the fact that the police department would take up more than 53% of the city budget.

After several nights of unrest, Garcetti on Wednesday reversed course, proposing a $150 million cut to the department.

The next day, Los Angeles Police Chief Michel Moore was already pushing back by questioning how his department could afford the cuts.

It was clear that the messy, public business of negotiating the future of policing would continue, perhaps even intensify.

That night, more people took to the streets across the state, their protests far from over.

Nigel Duara and Jackie Botts are CalMatters reporters, Manuela Tobias is a reporter with the Fresno Bee and Kate Cimini is a reporter with The Californian. This article is part of The California Divide, a collaboration among newsrooms examining income inequity and economic survival in California.

No Comments