18 Mar WCCUSD Charter School Committee Sets Priorities and Explores Updates to Board Policy

By Edward Booth

The recently formed West Contra Costa School District Charter School Committee on Monday discussed prioritizing the committee’s goals and reviewed draft updates to school board policy to align it with current charter school law.

The committee was formed in December. This was its second meeting, following one in January. School board members Demetrio Gonzalez-Hoy and Leslie Reckler sit on the committee with staff liaison Tony Wold, the district’s associate superintendent of business services.

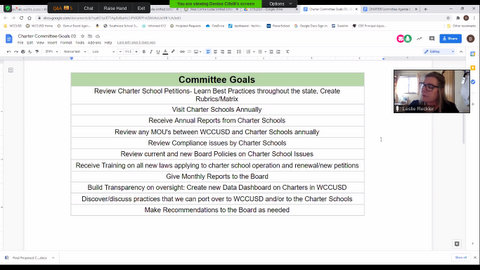

The committee first considered how to prioritize 11 potential goals. Those are reviewing charter school petitions and learning best practices throughout the states; visiting charter schools annually; receiving annual reports from the schools; reviewing Memorandums of Understanding between the district and charter schools; reviewing compliance issues by the schools; reviewing board policies on charter school issues; training on charter school laws; monthly reports by charter schools to the board; transparent oversight with a WCCUSD data dashboard on charter schools; to discover outside practices that can be used in WCCUSD; and to make recommendations to the board as needed.

Reckler said she’d prefer to tackle updating the policy first. She also liked the idea of the data dashboard transparency tool. Joseph Glatzer, a district teacher, said in a public comment that developing an updated charter school board policy is crucial and that handling compliance with policies and state law would naturally flow from the policy, once it’s established.

Gonzalez-Hoy said he’d like to receive the annual reports from charter schools, but also that some of the items could take quite a while to implement. The two board members agreed that focusing on the new charter policy was best to tackle first. They said that could be achieved by the end of the school year.

“I do think it’s going to take us a while to get through this and do it well while also engaging with the community,” Gonzalez-Hoy said.

Much of the meeting involved attorney Edward Sklar talking about recent changes to California charter school law and how to incorporate those changes into district policy. Assembly Bill 1505, he said, represents the most significant change. The bill went into effect July 1 — during the initial surge of COVID-19 — and needs to be codified into the board policy, Sklar said, though the law still applies in the district without being finalized in policy.

“The California Charter School Act passed in 1992, and for about 27 years, until 2019, the focus of the debate was what do district-operated schools look like standing beside charter schools? How do they compete academically?” Sklar said. “The reality of it was charter schools were creating incredible fiscal impacts on the districts themselves.”

Sklar said the law, perhaps most significantly, allows districts to deny charter school petitions on the basis of fiscal impact or community interest. Previously, board members weren’t allowed to consider either in the approval process, and could only decide to approve or deny on the basis of the school’s financial viability and academic program.

The ability for boards to deny charter petitions out of fiscal impact got a lot of media attention, Sklar said, partially because charter schools cost districts millions each year. A 2019 report by In the Public Interest done in partnership with WCCUSD staff estimated that charter schools cost the district $27.9 million during the 2016-17 school year.

Sklar said much of the shift in understanding of the role of charter schools in recent years, represented in the recent changes of the law, are related to a recognition of this financial impact on school districts.

But the reality of how the law turned out, Sklar said, means that school boards can only use fiscal impact as a basis of denial if the district has a negative budget certification. That means the district wouldn’t be able to meet its financial obligations for the remainder of the current fiscal year or the subsequent fiscal year. Alternatively, the district may deny a charter school on the basis of fiscal impact if they have a qualified budget certification, which means the district might not meet its financial obligations, but only if the certification would become negative if the charter school was approved. Determining whether a qualified certification would become negative has to be confirmed by the county superintendent, Sklar said.

Sklar said the board has discretion in how to define community interest in its policy. Wold said the community interest portion of the policy can be used by the board to define their philosophy of what a charter school should be. He added that the original vision for charter schools, as a sort of hub of innovation that could benefit all education, could be relevant to the section. The full board would need to be incorporated into the process, Wold said.

The revocation process for charter schools stayed mostly the same, but the renewal process now focuses heavily on academic performance, Sklar said. Community interest isn’t considered in the renewal because the schools, which have likely been in the district for a minimum of five years to need to renew, are assumed to be a part of the community already, he said.

Sklar said schools are split into three categories depending on their performance, which essentially determines whether they’ll be renewed. Mid-range performing schools are required to be renewed by the board for five years; an additional two years can be added on for high performing schools. The usual case where a charter revocation can happen is with low performing schools, but boards have the option to give those schools a two-year renewal to see whether the academic performance will improve.

Sklar added that the committee was probably ahead of the game talking about updating the board charter policy now. Because AB 1505 went into effect right in the middle of the pandemic, he said, school districts had other priorities they had to pay attention to at the time. Very few districts have updated their policy so far; the San Diego Unified School District and Los Angeles Unified School District are notable exceptions, but both are large districts with a heavy charter school presence.

No Comments