09 Mar With Climate Change, Comes More Potential Complications for People with Lupus

(Photo by Engin Aykurt on Unsplash)

By Julia Métraux

With the clock approaching midnight, Julia Irzyk could not fall asleep. She was playing solitaire, with her feet up on her La-Z-Boy sofa in her home in the Sherman Oaks area of Los Angeles. She was not just experiencing insomnia thinking about the state of the world: Her blood pressure rose to 195 over 110, well above the norm for most adults of less than 120 over less than 80, according to the National Institute of Aging.

That meant she was experiencing a hypertensive crisis, likely linked to her autoimmune disorder lupus. Emotional stress can affect blood pressure, so staying calm was important, yet Irzyk was failing miserably. During this episode in August 2022, her husband — her caregiver — was over 2,000 miles away on a business trip, in Chicago. Her dark gray cat, Disney, seemed to sense something was wrong but could not exactly help her receive emergency healthcare.

>>>Read: Caregivers Need Support — and for People to Get Vaccinated

What would happen next? Irzyk did not know. She took a “crap ton of medications,” as she describes it, including hydroxychloroquine and adalimumab injections to manage her symptoms. Still, these drugs couldn’t shield her against the effects of a heat wave. Did she need to break her rule of not going to the emergency room during COVID-19? How long would this flare last? Would she have to go back on prednisone?

With just her cat keeping her company, she needed medical advice. The heat, to Irzyk, felt “like a 40-pound backpack” she was “carrying around all the time.” She sent a message to her rheumatologist; she did not hear back. The doctor was likely asleep. Irzyk also wanted to be asleep. She was exhausted from running a talent agency during the day. But lupus health complications do not run on a convenient schedule. She spoke over the phone with her father, Mark Rothstein, the director at the University of Louisville’s Institute for Bioethics, Health Policy and Law. He told her to go to the emergency room if her 195 systolic blood pressure jumped to 200.

Irzyk, who is 45 and has lived with chronic pain for most of her life, suspects rising heat in Southern California worsens her lupus symptoms. Every summer, Irzyk knows that her body will have a flare-up of debilitating chronic illness symptoms, and she is terrified about how longer and hotter heat waves will affect her health. It took her close to two decades from her onset of lupus symptoms to get a diagnosis. Now, she had to figure out how to navigate that diagnosis with the ever-changing threats of climate change.

That August night, she avoided the emergency room and endured her symptoms until the flare passed. But as someone who has barely left her house during the COVID-19 pandemic, except to go into her office with a good mask, the heat was an unneeded pressure.

***

Around one in 1,000 adults, have been diagnosed with lupus in California. Heat waves and wildfires, worsened by climate change, exacerbate cardiovascular and respiratory issues and make managing autoimmune disorders and other chronic illnesses more difficult. And there may be many more undiagnosed, in part due to the ability of infectious diseases like COVID-19 to trigger chronic illnesses.

>>>Read: Richmond’s Most Vulnerable Can’t Escape Dangerous Air

There are three main types of lupus, all diagnosed through a combination of blood and urine tests. The most common form is systemic lupus erythematosus. Even without heat waves, lung problems, heart problems, kidney problems, seizures, chronic pain and exhaustion can be common complications in people who have SLE. When people with lupus have severe systemic involvement, which includes high levels of inflammation, they can also experience kidney failure.

Dr. Tom Bush, the author of an August 2021 paper on climate change and rheumatic diseases published in the Journal of Climate Change and Health and a rheumatologist at Santa Clara Valley Medical Center in San Jose, says there needs to be more research on autoimmune diseases and climate change. Facing heat waves and wildfires, he said, “at the same time that you have an immune system you’re fighting,” while also potentially being on medications that increase heat sensitivity, “could be a dangerous situation.” Medications that can make people’s bodies more heat-sensitive, which can include antidepressants and antihistamines, aren’t uncommon.

A small May 2013 study published in the Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology found that of 91 study participants with lupus, 81% experienced photosensitivity symptoms, meaning sensitivity to ultraviolet radiation. Monica Blied, a psychologist who lives with lupus and who serves on the medical advisory board of Lupus LA, tries to stay inside when the sun is at full strength. Photosensitivity is commonly associated with lupus. Climate change is also starting to affect UV radiation, and, according to researchers, “these effects will become more pronounced in the future.”

As a result, people with lupus who experience photosensitivity face a degree of isolation. “This is what the general population got to experience with the beginning of COVID, when we had to quarantine,” said Blied, who is based in Claremont, near Los Angeles, and herself has to sit out of activities that can trigger photosensitivity. To cope with the mental health effects of isolation and other debilitating lupus symptoms, she recommends that people reach out to lupus support groups and mental health providers.

>>>Read: Isolation Common Among Local Elders During Pandemic

Air conditioning in one’s home can decrease the risk of acute health episodes. A November 2010 study published in the American Journal of Epidemiology found that, when adjusting for socioeconomic factors, people who used AC in California during heat waves were less likely to be admitted to the hospital between 1999 and 2005 with issues like renal failure and acute cardiovascular issues.

Cooling centers, especially during COVID-19, aren’t a great solution. Contracting this infectious disease, especially multiple times, puts lupus patients at risk of developing more serious complications. Many have also been putting off care — Irzyk, for example, said she’s “never been so desperate to go to the dentist.” Lupus patients faced shortages of hydroxychloroquine at the beginning of the pandemic due to this medication being promoted as possible treatment for COVID-19. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention did walk back its guidance for this drug to be potentially used to treat COVID-19 in April 2020.

Rupa Basu, a heat epidemiologist at California’s Office of Environmental Health Hazard Assessment and one of the authors of the aforementioned study also notes, “Another thing that comes up is people don’t know that they should be using” AC as the heat rises. Or they cannot afford the cost of their energy bill. Grant and loan programs, such as the Low Income Home Energy Assistance Program, can be difficult to navigate.

When the temperature rises over 100 degrees Fahrenheit, anyone could experience adverse health events. Basu and other scientists, clinicians and public health services need to ensure people are aware of potential adverse health effects.

“It doesn’t really help if we’re just keeping it amongst ourselves and just keep going on with the research,” she said.

***

- During last September’s heat wave L.A. resident Julia Irzyk, who has lupus, said she felt felt “zero guilt about running the air conditioning, because the alternative is that I end up in the hospital, and I don’t see how that helps anybody in the long term.”

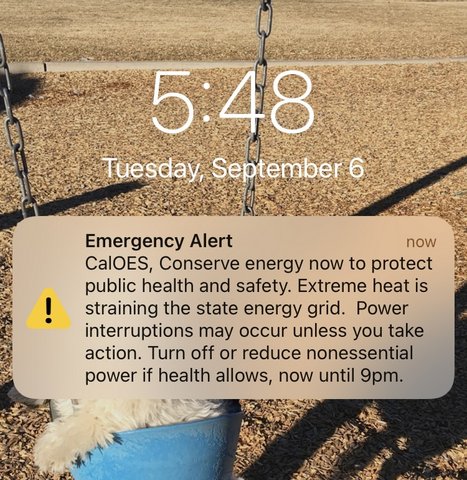

During the early September record-breaking heat wave in California, people across the state received a text urging them to conserve power, asking residents to “turn off or reduce nonessential power if health allows.” In Los Angeles, where the temperature reached triple digits even late into the day, Irzyk kept her AC on and her fans faced towards her, so she could at least minimize her dry-heaving.

“It’s no good if I’m dead,” Irzyk said. She felt “zero guilt about running the air conditioning, because the alternative is that I end up in the hospital, and I don’t see how that helps anybody in the long term.”

Irzyk’s plan, if her power got shut off or her AC failed, was to go to a hotel. This would be expensive and a hassle for her. And she already had to do it before.

Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, when her husband was shooting a commercial in Brazil, the AC went out. Trying to stay upright with a cane, she then had to “wrangle a cat into a carrier.”

Back up the California coast, not as many people have AC in their homes, no matter whether they could afford it. Basu, the epidemiologist who studies heat herself, does not have AC in her family’s home. “There are usually a few days throughout the year now we’re thinking, ‘Oh, maybe we should just get it,’ ” she said.

Some time later, after the brutal heat wave, the truth is, no one knows how many people died due to complications related to the heat wave. As the Los Angeles Times reports, this falls in the pattern of a state that is already hit by acute weather events but struggles to keep track of heat-related illnesses and deaths.

A lot more in-depth research is needed on how autoimmune disorders like lupus respond to rising heat temperatures. As it stands, communities of people with chronic illnesses do their best to check in with each other. On Twitter, many share their journeys, tips, frustrations and hopes using hashtags such as #NEISVoid (the acronym stands for No End In Sight), the political #CripTheVote, and the general #DisabilityTwitter. For instance: It’s important to keep some medication around 70 degrees. Some people also send encouraging messages to those applying for programs like disability benefits, telling them it’s not unusual to get rejected the first time, for instance.

>>>Read: Disabled Twitter Users Face Potential Loss of Community

The lack of chronically ill and disabled people involved in climate change planning is a major problem. The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency notes “climate change effects on people with disabilities have not been studied as much as other vulnerable populations.” But this population is especially vulnerable. People face a higher risk of health complications and more difficulty moving when climate change forces displacement. A lack of recognition of the challenges disabled people face is part of the issue. As noted by disability activists at the 2022 United Nations Climate Change Conference, the U.N. still does not recognize the disability community as a group vulnerable to the effects of climate change. How much research is needed before people in power act to protect those who are already struggling due to acute weather events?

Some nondisabled environmental activists say that everyone has a responsibility to limit power, including AC and heating. But this leaves out people who do not have a choice. Irzyk relies on community support to help her take care of her needs. This includes a parking attendant near her office who makes sure she is able to park in an area protected from the sun on hot days.

Public health officials need to do their part as well. Increased attention and research is vital, which groups such as Lupus LA and other patient advocacy organizations push for.

“This is helping to keep them alive, so they can fight another day with their chronic illness,” Blied said.

No Comments