23 Dec California Redistricting: What to Know About the Final Maps

California voters have the brand new districts they’ll use to elect their members of Congress and state legislators, after the state’s independent redistricting commission voted unanimously Monday night to approve its final maps.

These districts take effect with the June 2022 primaries and continue for the next decade. Redistricting happens once every 10 years, after every census, to ensure that each district has the same amount of people. It’s the second time that California’s redrawing is being done by a 14-member independent commission.

But it hasn’t been easy, or without contention.

In addition to balancing population numbers, the commission must comply with the federal Voting Rights Act, ensuring that no minority group’s vote is drowned out. And to create fair maps, the commission didn’t consider current district lines and isn’t supposed to weigh partisan politics. In some cases, it puts incumbents into the same district, or forces others to appeal to new voters to be re-elected.

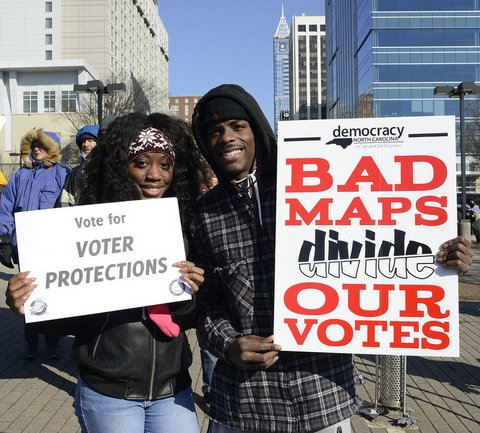

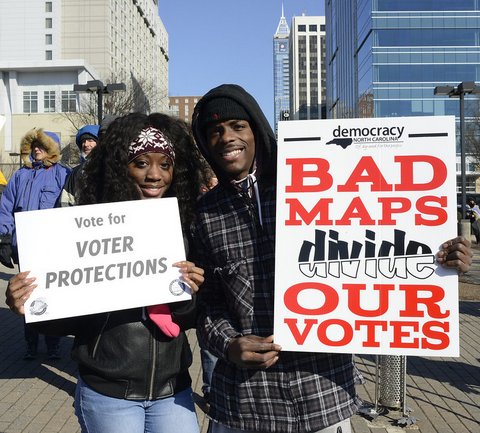

>>>Read: Redistricting Plays Key Role in Minority Voting Power

Particularly on the congressional level, that could help shift the balance of power between Democrats and Republicans. In the U.S. House, three California Democrats are among the 23 Democrats nationally who have already opted not to run for re-election in 2022. Combined with redistricting done by Republican-led legislatures in other states, that could tip the House in favor of the GOP.

Some California Democrats have blasted the “unilateral disarmament” of their power, though an initial analysis by the Cook Political Report says the new congressional map helps Democrats.

The commission’s deliberations have been different from the last redistricting, in 2011, in large measure due to advances in technology, plus social media, particularly Twitter.

In 2021, it is far easier for advocacy groups and others to submit their own maps — and respond to mapping decisions in real time. As they did live line-drawing, commissioners referenced these maps, along with the feedback they were getting.

The commission was under the pressure of a court-ordered deadline to submit the maps to the secretary of state by Dec. 27 despite a nearly six-month delay in the release of census data. In the last few weeks, the panel held a number of marathon sessions late into the night to hear public comment and try to incorporate competing testimony into the maps.

>>>Read: New Census Data Shows U.S. Has Gotten More Diverse

Commission chairperson Alicia Fernández acknowledged that there were constraints and disagreements along the way, but said she was proud of the commission’s work given the rules they were under.

“There was robust discussion in terms of how these maps should be drawn. We know that not everyone will be happy, but I feel that they are fair maps for Californians,” she told CalMatters.

Now, the maps must sit for three days for public input, though no further changes are permitted, said Fredy Ceja, communications director for the commission. In the meantime, the commission will complete its final report to deliver to the secretary of state.

Even after that happens, the new districts are likely to be challenged in court. And their real impact depends on what voters decide.

James Woodson, policy director for the California Black Census and Redistricting Hub, said the fight for Black political power in California is far from over.

“Census and redistricting is sort of a two-part fight,” he said. “First, it’s making sure that resources came to our community and making sure they had an opportunity to win political power. Now, it’s about getting out the vote in 2022 and the long-term policy pieces that are moving.”

Here’s a first look at the new districts:

Congressional lines

Slower population growth in California means the state lost one of its 53 U.S. House seats this year — though COVID-19 may have caused an undercount of Black and Hispanic residents.

That added another challenge to deciding congressional districts. The population numbers must be exact: There can’t be more than a one-person difference between districts to make sure everyone is represented equally.

Trying to meet all the criteria — equal population, Voting Rights Act compliance, communities of interest and compact districts — in a state with California’s diverse population and geography made the task difficult.

To keep California’s less populous mountain communities together, for example, an earlier version of the maps showed a district stretching from the Oregon border to San Bernardino County. While compactness is one of the lower-ranking criteria, the district still raised eyebrows and was later revised.

Also drawing attention: How redistricting can topple the political dominoes. On Dec. 16, Democratic Rep. Alan Lowenthal announced he would not seek reelection. The next day, Long Beach Mayor Robert Garcia declared for the seat and quickly rounded up support. And on Monday Rep. Lucille Roybal-Allard of Downey, who in 1992 became the first Mexican American woman elected to Congress, announced that she is retiring after her current term after she was redrawn into the same district with Garcia.

The growing power of Latino voters — and recognizing that in the new maps — has been a constant theme of the redistricting process. A projected 16 of the 52 House districts have a Latino voting-age population of at least 50%.

Pablo Rodriguez, founding executive director of the Communities for New California Action Fund, noted that in the Central Valley there are three new strong Voting Rights Act congressional districts with more than 50% Latino voters.

“For the Central Valley the outstanding question will be: Will the new Latino majority districts create the environment for the first Latino/a congressional representative to be elected to Congress within the next ten years?,” Rodriguez said in a statement. “Confidently, I say yes to not just one, but likely 3.”

But not everyone is a fan of the congressional map. Former redistricting consultant Tony Quinn said some of the new maps could disadvantage Latino candidates, such as the district that pairs eastern San Jose with Salinas.

Quinn said he doesn’t believe the Voting Rights Act required the kinds of districts the commission has drawn.

“It didn’t seem to me that the map needed to be torn up the way it is,” he said. “They way overdid it, especially in L.A. County.”

State Senate districts

While congressional districts each have about 760,000 people, state Senate districts are larger, with nearly 1 million Californians. For example, one encompasses California’s entire border with Mexico. There’s also more leeway — a 5% deviation from the ideal population.

That means that, while the commission tried not to put communities with competing interests together in other maps, it paired some in the Senate map, such as Fresno and Kern counties.

Three Senate districts are going from a Democratic advantage in voter registration to a Republican majority, while one favors Democrats more. Republicans need to flip at least five seats in the Senate, or seven in the Assembly, to end the supermajority that allows Democrats to approve tax increases or put constitutional amendments on the ballot without a single GOP vote.

The Senate map also pits some incumbents against each other, according to an analysis from political data firm California Target Book. For example, Democrat Connie Leyva’s Chino residence gets drawn into Democrat Susan Rubio’s district.

The commission’s sixth and last criteria for redistricting is nesting — placing two Assembly districts into one Senate district where possible. In theory, that makes Senate mapping easier. But because the commission placed a higher priority on other criteria, this time, only two Assembly districts were nested into a Senate district, in Northern California.

In a Dec. 13 letter to the commission, redistricting expert Paul Mitchell wrote that nesting conflicts with trying to comply with Voting Rights Act requirements.

The commission wrapped up its Senate maps on Saturday to allow time for numbering the districts, a complicated process to limit the number of voters who would have to wait six years to vote for senators since they serve staggered four-year terms.

Assembly lines

While the Democratic majority in the state Senate might shrink under the new map, Democrats’ grip of the Assembly could tighten.

They now hold 60 of the 80 seats. The new Assembly map creates 63 solid Democratic seats, according to an analysis by California Target Book.

According to the analysis, two Democratic-majority districts in Southern California become stronger Republican districts; they’re now represented by Republican Phillip Chen of Brea and Democrat Cottie Petrie-Norris of Orange County. Another two flipped from Republican to Democratic-majority districts; they’re represented by Republicans Janet Nguyen of Huntington Beach and Marie Waldron of Escondido.

Advocates for the LGBTQ+ community said the maps include big victories across California. In the Assembly map, bringing Hollywood and West Hollywood together gives the community a chance to elect a representative from the community, said Samuel Garrett-Pate, managing director of external affairs with Equality California, adding that the group’s former director, Rick Chavez Zbur, was well-positioned to run.

Board of Equalization

With just four state Board of Equalization districts, they are far less complex to draw.

The board is tasked with ensuring that taxes across different counties are uniform – alcohol and beverage taxes, for example. Because of the county-specific policies, the commission tried to keep as many counties as possible intact. For example, densely populated Los Angeles County is one district by itself.

For these lines, there was little drama at the redistricting commission — and certainly nothing like the fights over congressional and legislative districts.

Monday night, closing out their review of the maps, it was an emotional moment for some commissioners.

“I’m so proud of the work that together we have completed to serve all Californians. Despite a difference of opinion at times, there was always commitment to our common goal — to the goal of creating representative and fair maps for all Californians,” commissioner Pedro Toledo said as he made the motion for a vote.

”We accomplished all of this while in the midst of a global pandemic and unprecedented adversity that impacted us all personally, impacted our communities and our state,” added Toledo, a no party preference voter and chief administrative officer of Petaluma Health Center.

After Dec. 27, the commission expects it will reconvene not only to defend its maps against any legal challenges, but to work on a report that could make the process smoother for the next redistricting.

“We did receive community of interest testimony that did conflict so obviously there are some people that are not going to be happy,” said Fernández, a Republican from Yolo County. “We have more VRA districts than there currently are, we listened to more people than the prior commission. We took all the info to heart and worked together to build these maps.”

This article was originally published Dec. 12, 2021, by CalMatters and shared via the CalMatters Network. It has been reproduced with permission.

No Comments