02 Apr Voting Districts Are About to Be Redrawn. Here’s Why It Matters

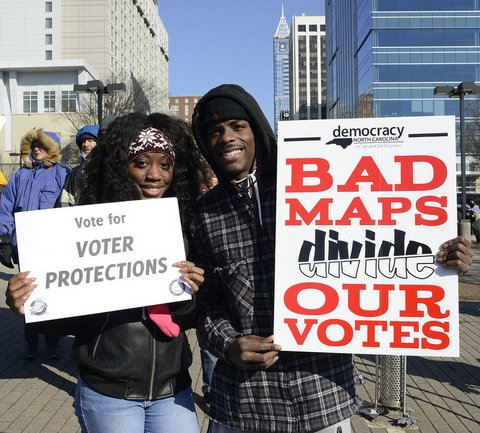

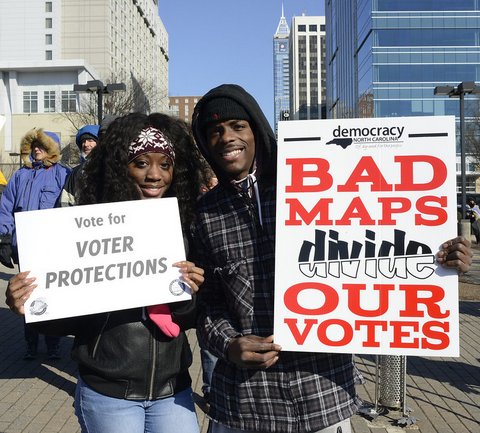

(“2016 Moral March on Raleigh 24” by Stephen Melkisethian under CC BY-NC-ND 2.0 license.)

By Danielle Parenteau-Decker

Voting districts play a key role in whether people can elect candidates who best represent their interests. This year, those lines can be redrawn, which could severely impact the voting power of racial and ethnic minorities.

On the surface, population determines voting districts. Every 10 years, the U.S. census is used to segment areas with roughly the same amount of people. That is supposed to help ensure equitable representation.

But population alone does not establish what each district looks like. There are a lot of factors at play.

Districts are often purposely drawn to keep someone in — or out — of power, whether that be officials or the public.

From Congress down to school boards, most politicians at the federal, state and local levels are elected through district-wide votes, so there’s a lot at stake.

“The decisions made with redistricting can determine not only policy but also policy-makers,” said Thomas A. Saenz, president and general counsel of the Mexican American Legal Defense and Educational Fund.

Indeed, where mapmakers draw the lines influences who runs for office, who gets elected and how responsive officials are to a community’s needs, Terry Ao Minnis of Asian Americans Advancing Justice said.

>>>Read: Richmond Residents Pick Favored Voting District Maps

Saenz and Minnis, senior director of census and voting programs, spoke on a panel Ethnic Media Services hosted March 26. At the heart of this discussion about redistricting was what it means for racial and ethnic minorities.

“We are committed to minority rights in this broader system of majority rule,” said Justin Levitt, a professor at Loyola Law School and creator of the website All About Redistricting.

Minorities’ voting power can be diminished through redistricting in two key ways: They can be divided among separate districts or packed into a “supermajority-minority” district, said Leah Aden, the deputy director of litigation for the NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund.

With too few people in a given area, they can’t influence election results. Or if minorities’ votes are concentrated into one area, it lessens the scope of their impact.

Redistricting can be used not only to limit certain voters’ influence but also to keep someone in office. Sometimes, the two go hand-in-hand.

Saenz described a situation involving neighboring districts in the San Fernando Valley area of Los Angeles County. One that had become majority Latino probably would have reelected a white incumbent, but it likely would have cost him more money, Saenz said. So Latinos were “broken into separate districts to diminish their voting power.”

“We would hope that growth of communities of color [would help], but it doesn’t always work that way,” Saenz said.

Even Latino legislators supported the move because they believed it was more important to help the incumbent stay in office.

Indeed, some defend questionable districting decisions by saying they are necessary to “protect the party,” Aden said.

“They’re basically excuses for racial discrimination,” she said of that and other reasons.

According to Levitt, lawmakers in most states hold primary control over redistricting.

Saenz said incumbents need to be removed from the process especially in small districts where they are more likely to collude to keep each other in power. That’s even if they belong to different political parties and have different beliefs.

Things work a bit differently, however, in California: An independent commission draws districts. The 2020 Citizens Redistricting Commission has 14 members: five Democrats, five Republicans and four with no stated party preference.

Aden said the California Voting Rights Act gives her hope because it ensures Latino, Black and Asian voting power.

Saenz was less enthusiastic. He said the law only applies to challenging at-large elections. Because of that, he added, many jurisdictions converted to district elections and are “drawing lines without court supervision” for the first time.

But obstacles during the 2020 census threw a wrench into not only that process but redistricting as well.

The pandemic and politicization slowed the census down, diverted resources and made people less likely to participate, Saenz said. The Trump administration’s failed attempt to include a citizenship question on the census served to exclude many minorities.

Those delays could mean bodies in charge of redistricting might be unable to meet deadlines.

To make sure redistricting works for the people, panelists said public participation is crucial.

Fatigue, burnout and lack of education could all make people less likely to engage, Minnis said, encouraging people to work with their neighbors and testify at public meetings.

“Community engagement is one of the biggest worries,” she said.

California residents can find out more and send input to the redistricting commission at wedrawthelinesca.org.

No Comments